|

HISTORY

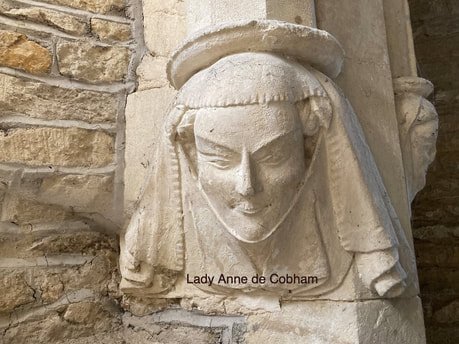

There has been a Saxon church in Langley Burrell from the 9th century - the lower two feet of the wall at the corner of the present south wall of the nave and the porch is believed to be Saxon work. The nave was rebuilt in c.1185 when an aisle was added and the porch also dates from this time. In the porch are the remains of a holy water stoup and there is also a door into the adjoining tower. The chancel is c.1225-50 but the chancel arch dates from 1290 when the sedilia (priest's seats) and small chancel windows were added. In the 1260s the nave and aisle were altered and extended while c.1440 both were re-roofed with a wagon roof set on carved corbels. There are traces of medieval wall paintings below these corbels in the nave. The tower is early 14th century and contains four bells dated 1607, 1618 with two of 1628. On the tower wall are wooden panels displaying the Ten Commandments, the Lord's Prayer and the Creed. In c.1460 Perpendicular windows were added to the church, a rood erected and the porch provided with roof vaulting with a central boss of the Risen Christ. The south chapel was built in c.1480 along with the arches into the tower and chancel. The chapel contains many Ashe family memorials and the table is probably a 17th century communion table. Little seems to have been done to the church in the 16th century after the work of the previous century and, apart from the bells and former communion table the only 17th century feature is a superceded font near the pulpit. In the 18th century the balustraded communion rails and gate were erected and the fielded panelled pulpit built. There were many alterations in the latter half of the 19th century and most took place after Robert Kilvert became Rector in 1855. His son Francis Kilvert, the diarist, was curate to his father in 1863-4 and again in 1872-6. The Victorian font dates from c.1860 and after the Bishop of Gloucester said that the church was choked with high pews and inconvenient for a confirmation (of Squire Ashe's daughters) in 1871 work was undertaken in the interior of the church when the gallery was removed and a stove placed in the church. In 1796 the Rev. Samuel Ashe had presented the church with a bassoon but in Kilvert's time Squire Ashe disliked any music in church other than the human voice. George Jefferies had led the singing for 40 years but in 1874 when his voice began to crack Squire Ashe refused to pay him any more and the Kilvert family, with financial support from the village, bought and installed a harmonium despite initial disapproval from the Squire. This lasted until 1901 when it was replaced by a Positive organ, which in turn was replaced with an organ made by Roger Pulman of Suffolk in 1980. Francis Kilvert died at the age of 39 as Vicar of Bredwardine and his father, Robert, died in 1882 at Langley Burrell. He and his wife Thermuthis are buried in Langley Burrell churchyard. The church has been very fortunate in its 19th century restorers. Two of the best church architects working in Wiltshire were involved at the end of the century. In 1890 C.E. Ponting carefully restored the chancel and underpinned the tower, while in 1898 Harold Brakspear restored the nave and aisle. There were further repairs to the tower in 1926, electric lighting was installed in 1956 and a new heating system in 1964. The church has a light and 'airey' atmosphere, but pleasant as it is, it lacks certain modern facilities: There is a need for a new lavatory that is accessible to all as the existing outbuilding was only meant to be a temporary structure: The latest news in December 2022 is that a grant has been agreed with the Parish Council to rebuild the toilet block and make it available as a facility on a new Heritage Trail. That is not the end of our efforts to protect and develop this site for future generations and if you are prompted to get involved please let us know. To do so would be to follow a centuries-old pattern that accepts responsibility for our heritage and of course, for doing God's work in our community. The de Cobham Conundrum The Middle Ages were a time when religious dissent was risky and often proved fatal. Before the Protestant Reformation and the emergence of tolerance, St Peter's like any other church, could have witnessed such persecution, and indeed, on display in the porch and in the nave it is said that a certain Sir Reginald de Cobham was burnt to death nearby for his early Lollard affiliation, (as a follower of John Wycliffe). This apparent record prompted some recent research by a member of the congregation, assisted by the Wiltshire History Centre in Chippenham to check its veracity. Thanks to evidence gleaned from the internet and other sources, it seems clear that no such event, as described, took place. The confusion is explained, in part, by the fact that there were quite a number of 'de Cobhams' with similar names and titles. The first Baron Cobham - 'Reynold' - 1295-1361, married Joan de Berkeley (from Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire?) and was based on the Kent-Surrey border at Lingfield. His tomb is in the local church. He was followed by another Reynold de Cobham, 2nd Baron of that name - 1348-1403. The third Baron Cobham (1381-1446) is of much more interest to us at St Peter's: Although living at Sterborough Castle, Lingfield, he was patron of St Peter's (and no doubt many other parish churches). Perhaps he was a particularly pious person as he not only made significant improvements to the fabric of his local church, but also to St Peter's. Indeed, rather hidden from view, high above the arch leading from the vestry area to the side chapel are two stone corbels: A man and a woman with life-like early medieval appearance. Identities unknown? Well, perhaps no longer. The impressive tombs at Lingfield have effigies that are facially so similar that combined with the factual link with the church, their identities are most likely to be Reginald and Anne de Cobham. Which leaves the question of who, if anyone, was martyred for their faith? That was Sir John de Cobham, also known as Lord Oldcastle, who was burned in London in 1418. He had married the heiress Joan de Cobham in 1408 and had become a Lollard, but as history often demonstrates, motivations for action may be complicated and sometimes contradictory: In leading a rebellion against King Henry Vth he made a fatal mistake. So was he a martyr after all? Interestingly, through his marriage he had acquired estates in Wiltshire, such as at Broad Hinton, so there was some local link with this man. |

Address:

|